Jonah Sacks

Director, Architectural Acoustics Group

Studio A | Market Co-Leader

Principal

Some version of this statement has appeared in countless pop science articles and on the lips of esteemed members of the design community, particularly when discussing rooms for music. What does this statement mean? What leads people to talk about our discipline this way?

The word “dark” is intended, I think, in the sense of invisible or mysterious. Sound, after all, is not something we can see. This is a particular challenge for the design community, which is by nature visually oriented. While nearly all of us experience sound in our environment, we often struggle when using words to describe it.

The “art” of acoustics focuses on illuminating the subject. As acoustical engineers, we understand how sound behaves in a certain way, but it sometimes requires special ingenuity and even “art” to explain our work to others.

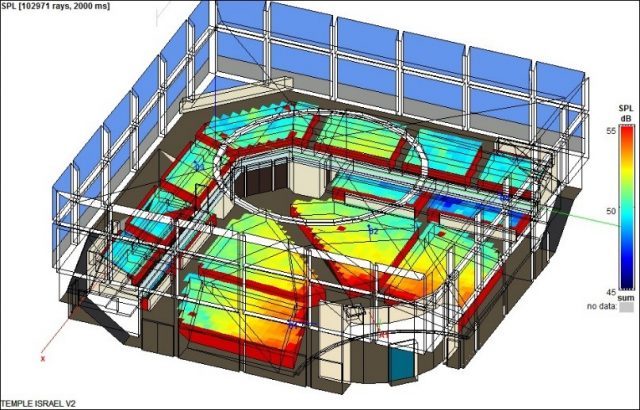

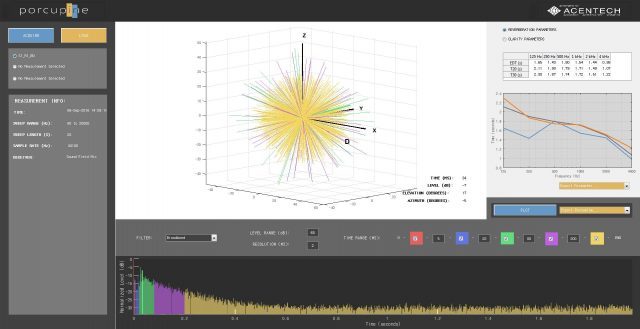

This is particularly important with rooms for music. Words like warm or clear connote positive aspects of the sound of a music room, while muddy or thin connote negatives. These words describe the subjective experience of listening to music in a room, which is a matter of aesthetics, emotion, and color. We acousticians also use words like reverberant, dry, and enveloping, which are terms of art that describe aspects related to acoustical design features of rooms. Numerical metrics such as reverberation time (RT), early decay time (EDT), strength (G), or lateral fraction (LF) describe a room’s acoustical behavior in an even more technical way. These metrics are useful because they are measurable and, in some cases, calculable, but they do not correspond directly to the listening experience.

Words and numbers can only go so far to help us communicate about listening to music. As comedian Martin Mull put it, “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” Or something like that.

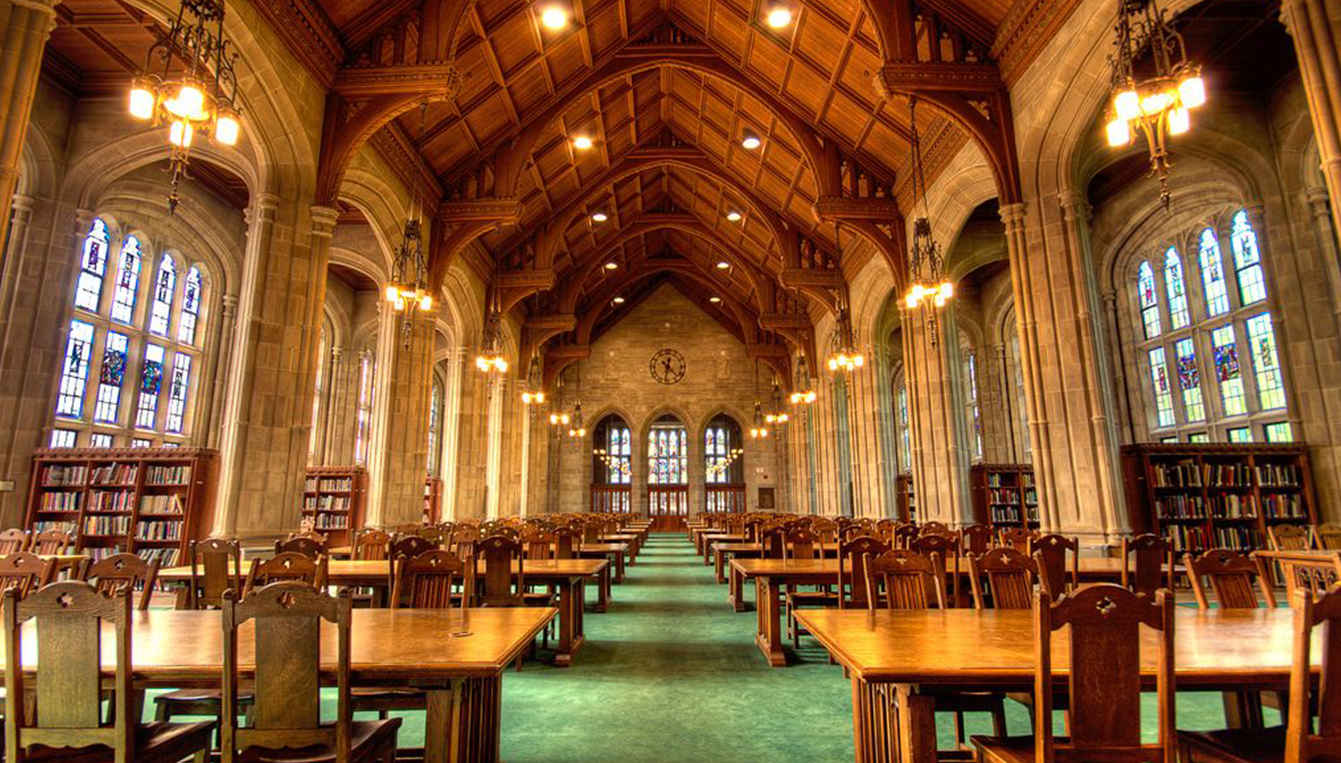

This is why it is so important, at the start of any project that includes design of a music performance room, to establish common vocabulary and to do the necessary work to understand one another. This is most possible among people who are experienced in the same music performance tradition, and who have some familiarity with the same music performance spaces. These may be local music halls on a college campus or famous international halls frequented by touring professionals. Often, it is useful to conduct a listening tour of relevant music rooms with project leaders. This also provides an opportunity to discuss in detail the intended uses of the room: the styles of music and the size and composition of the ensembles. The goal is to build a set of shared listening experiences and understand how they relate to the project at hand.

It can also be helpful to conduct virtual listening tours, such as listening to the results of measurements of existing rooms or computer models of designs, rendered with appropriate audio content. At Acentech, this listening process is called DListening, and we find it useful for comparing the sounds of different rooms or design choices.

Once we’ve established for what and for whom we are designing, we can agree on the acoustical goals of the project, on how our room should sound, and what excellent acoustics means to this particular user group.

Acoustical design is neither science nor art, though it draws on both. It is collaborative design, and we use many means and methods to work with others to establish common goals and achieve them. A dark art? No. If sound may sometimes seem dark, our art is to illuminate it.