James D. Barnes

Principal

Across the United States, cities are growing denser, mixed-use developments are proliferating, and under-used lots and buildings are being transformed into vibrant residential, commercial, and pedestrian communities. While this urban renaissance brings vitality and innovation, it also intensifies one persistent challenge: noise.

A consistent message across the case studies described below is the value of early integration. Addressing acoustics during design is vastly more efficient—and effective—than retrofitting after complaints arise. Early coordination allows for design strategies such as buffer zones, rooftop layout optimization, and the specification of low-noise equipment before installation.

The future of quieter cities depends not just on new technologies, but on integrating acoustics as a design priority, not an afterthought.

The urban soundscape is changing. As cities electrify, densify, and diversify, acoustical engineers are reimagining how to balance function and comfort. Facilities once hidden on the urban fringe now sit beside housing, parks, and universities. Each project presents both a challenge and an opportunity to apply acoustic science for social benefit.

At the 2024 Technology for a Quieter America (TQA) workshop, hosted by the National Academy of Engineering and organized by the Institute of Noise Control Engineering (INCE-USA), I shared my insights in a workshop, “The Impact and Control of Noise Generated by Commercial, Institutional, and Industrial Activities.” Drawing from decades of community noise consulting experience, I highlighted emerging patterns in urban noise sources, presented case studies of complex projects, and explored strategies for reducing their acoustic footprint.

Most urban environmental noise is not intentional—it’s a byproduct of essential work. Cooling towers, air-handling units, exhaust fans, condensing units, pumps, and generators keep buildings comfortable and processes running. Yet their collective hum, whir, and rumble can have far-reaching acoustic impacts in densely populated environments.

In modern cities, these sources are concentrated across commercial, institutional, and industrial facilities—often in close proximity to residences, hotels, and public spaces. While many of these systems are stationary, others, such as trucks or service vehicles, introduce mobile noise into the mix. The majority of these sources are performing useful work—but the noise they generate is an unwanted byproduct. The challenge lies not in stopping this work, but in managing its disruptive consequences through thoughtful engineering and planning.

Noise control solutions are divided into three fundamental categories—Source, Path, and Receiver—a framework widely used in acoustical engineering and refined through decades of practical application.

Hospitals and medical campuses epitomize the acoustic complexity of urban institutional environments. A typical hospital rooftop may host multiple wet cooling towers, exhaust fans, and air-handling units—all running continuously to support critical infrastructure.

In such cases, residents within the hospital are generally insulated from exterior noise, but nearby communities are often exposed to cumulative sound levels. While urban environments generally include a degree of “masking noise” from traffic or transit that can reduce perceived loudness, every new mechanical system installation must be carefully modeled and mitigated to ensure compliance with local noise limits and community expectations.

Few sectors illustrate the evolution of city noise challenges better than biotechnology. Once confined to suburban industrial parks, today’s biotech labs and research facilities are increasingly embedded within urban neighborhoods—near universities, hospitals, and innovation districts.

This Biotech Facility case study demonstrates a rooftop HVAC system designed for a life sciences lab in a mixed-use district. Surrounding the site were hotels, condominiums, and other labs, creating a dense acoustic ecosystem. Initial modeling projected noise levels of 64 dB(A) at a nearby hotel and 52 dB(A) at the closest residential condominium—values exceeding the 50 dB(A) nighttime limit.

Our mitigation approach focused on reducing noise at the source rather than relying on barriers, since barriers would be ineffective for upper-story receivers like hotel rooms. Solutions included equipment specification, vibration isolation, and the use of quieter fans and VFDs. This case underscores how proactive modeling and collaboration between acousticians, architects, and mechanical engineers can prevent costly retrofits later.

Mixed-use developments—a signature of 21st-century urban planning—create new layers of acoustic interdependence.

This project combined street-level retail with multi-story residential units above. The building’s heat pumps and emergency generator had to serve both commercial and residential tenants without exceeding local limits.

Complicating matters, the generator was sited near a commuter rail line and directly across from homes. Through detailed modeling and targeted mitigation—including acoustic enclosures and silenced ventilation paths—the design met code while preserving community relations. This case highlights how early noise modeling can ensure that density and livability coexist.

Even facilities that the public rarely notices—such as telecommunications hubs—pose distinct acoustic challenges. These buildings often operate 24/7, with mechanical systems cycling between high and low load conditions.

In this case study, we see a rooftop cooling tower and an indoor diesel generator located adjacent to a residential neighborhood.

Though the generator operated only during power outages, the city required compliance with the daytime residential noise limit of 60 dB(A). Mitigation measures included an acoustically rated enclosure, intake and exhaust silencers, and interior wall treatments. After these mitigation measures were installed, the neighbors were quite pleased with the outcome—a testament to how engineering and transparency can strengthen community trust.

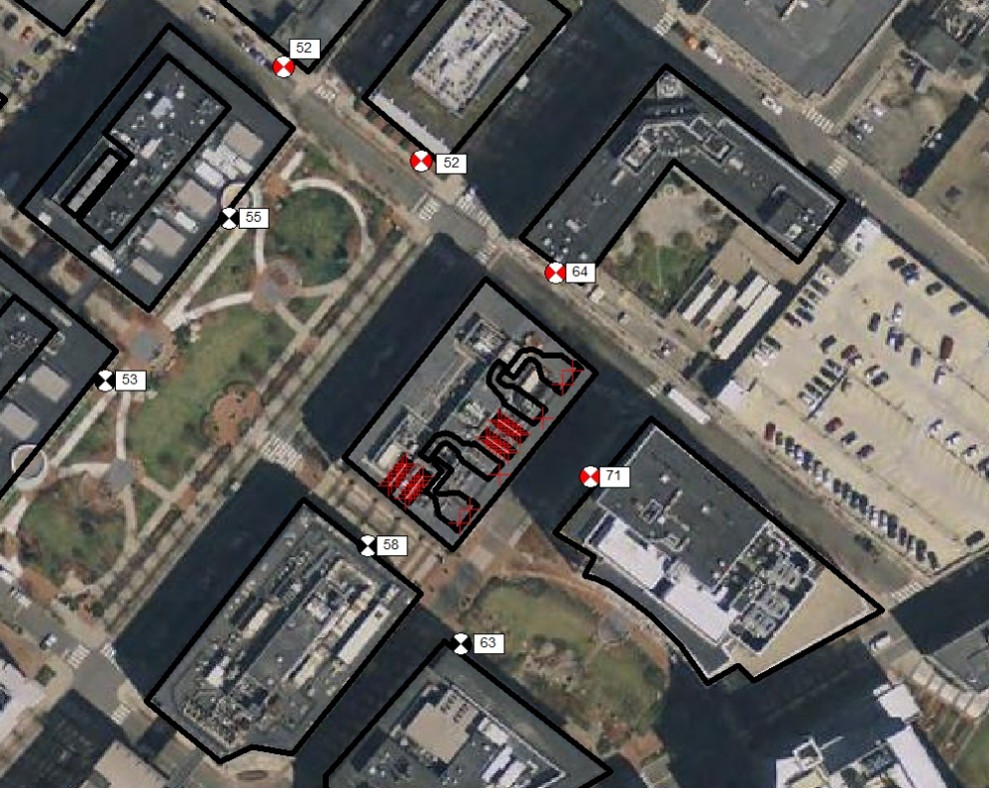

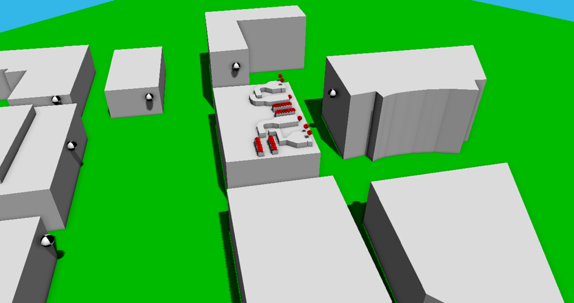

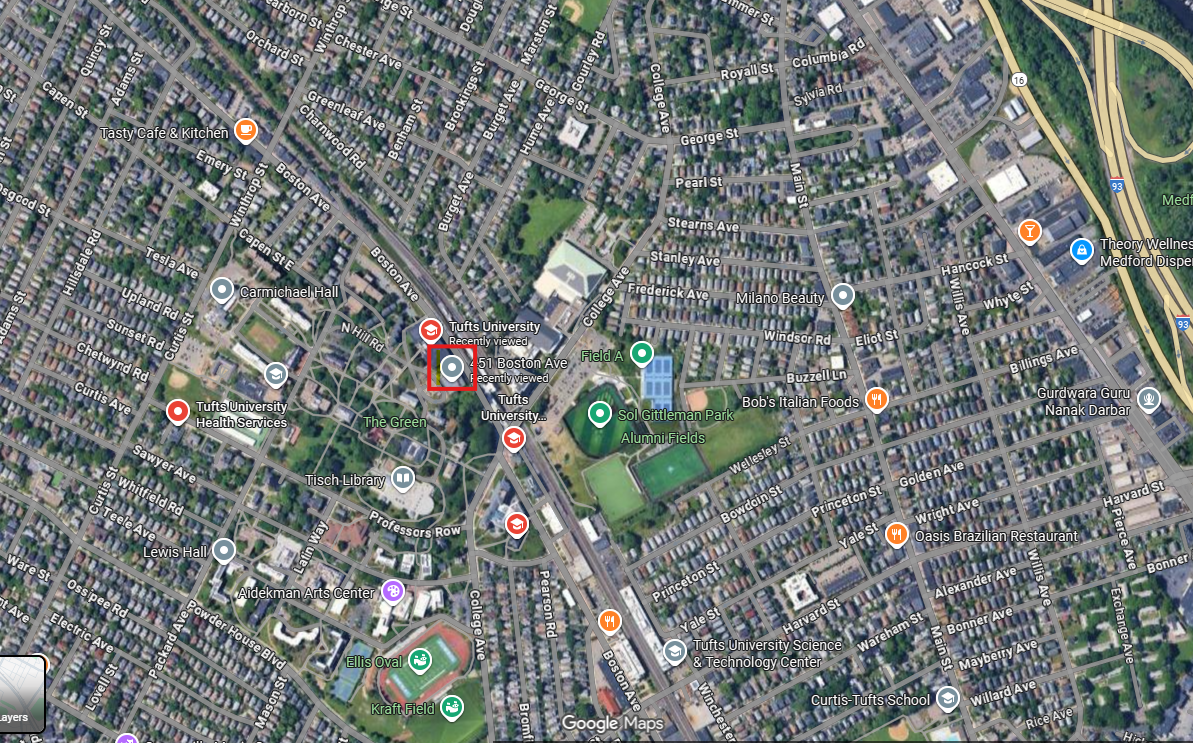

This final example represents the scale and complexity of noise control in large, multi-decade urban redevelopment projects. Located on a university campus, the facility houses cogeneration systems, boilers, ventilation fans, and cooling towers—all significant noise sources.

Here, the challenge was holistic: design noise control measures to meet near-term requirements while anticipating future changes in the surrounding land use. Treatments included acoustically lined ventilation systems, rooftop noise screens, and the strategic placement of mechanical rooms within the building envelope.

Managing the sound generated by this facility is a large, ongoing effort. The successful outcome of this project demonstrates how acoustics must evolve alongside urban transformation—balancing energy resilience with environmental quality.

At Acentech, we believe that designing a quieter America isn’t merely a technical pursuit—it’s a civic one. By aligning engineering innovation with community well-being, we can ensure that cities remain both vibrant and livable.